At the National Weather Service in Pittsburgh, someone is always watching.

“Mother Nature doesn’t take weekends, midnights, holidays off, so we can’t,” NWS warning coordination meteorologist Fred McMullen often says.

He’s part of a team of 20 meteorologists and staff that runs the weather office in Moon Township in 24-hour rotating shifts, making forecasts, collecting data, and issuing public watches and warnings.

When your cell phone blares with an emergency weather alert, it’s because they pushed a button, notifying a targeted area. NWS staff wait to hear their own phones to confirm that an alert’s gone out successfully — “it’s almost instantaneous,” McMullen says.

One of 122 regional NWS offices in the United States and its territories, the Pittsburgh weather service station covers not only Pittsburgh, but 35 counties with a total population of 3.5 million. The office’s “county warning area” spans three states including eastern Ohio, southwest Pennsylvania, and the northern panhandle of West Virginia.

The scope of their responsibility, according to McMullen, means they take great care when they draw a polygon, also known as a “threat box,” the red or orange shape that appears in their graphics. The polygon represents the area forecasted to be in the path of dangerous weather, which then gets an emergency alert reaching every phone in the area through geofencing.

On May 8, three tornadoes touched down near Pittsburgh overnight — including the first-ever tornado in Hancock County, W. Va. on the Pennsylvania border, which swept through with 130-mile-per-hour winds — and they had to make the call on who to wake up in the early hours.

“There was talk, you know, it’s one in the morning,” McMullen remembers. “Is this storm going to strengthen, weaken? Should we pull the polygon into the city of Pittsburgh, making 1.2 million phones go off?”

Pittsburgh City Paper visited NWS Pittsburgh following the recent spate of severe weather. After an onslaught of tornadoes, including one striking the Pittsburgh Zoo — the first tornado within city limits since 1998 — and other unusual and intensifying weather, NWS seems to have been catapulted into the spotlight. I was curious to see if their work and its stakes are changing alongside Pittsburgh’s weather and climate change as a whole.

The first thing to know about meteorologists, McMullen says, is “we’re big fans of data.” Historic data at NWS Pittsburgh dates back to 1870, making it one of the region’s longest-standing climate sites. (Fun fact: the station uses the shortcode PBZ to distinguish itself from PIT, the airport, which takes additional readings to inform air travel).

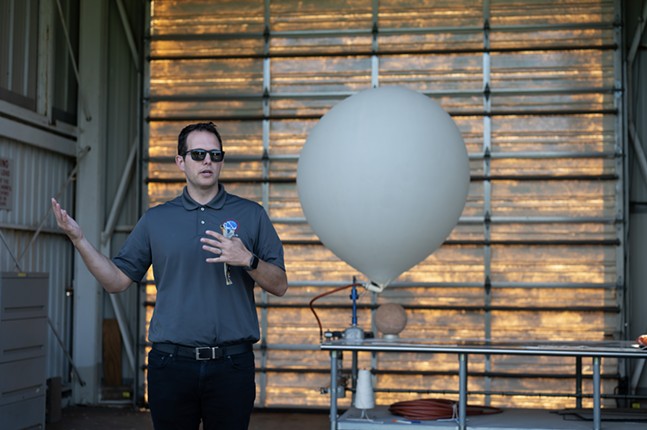

Every day, the weather station office, converted from a three-bedroom house in 1980, collects data from the region’s only radar tower (a white dome that looks like a volleyball), a temperature sensor, and a rain gauge that’s checked every four hours. In winter, they measure snowfall duration and depth with a big ruler and use a dowel rod to test ice accretion. And every morning and evening in the station’s detached garage, someone fills a weather balloon with hydrogen, ties it to a parachute — “like playing Army guys,” McMullen says — and launches it 100,000 feet into the stratosphere to compute humidity, pressure, and wind.

The consistency and longevity of their data collection enables NWS meteorologists to determine when records are broken and closely observe “the anomaly of the weather events.”

Ask an NWS meteorologist about the connection between Pittsburgh’s recent extreme weather and climate change, and you’re liable to get a multi-pronged answer with several data points.

Rain rates are increasing, McMullen confirms. In April, Oakdale, Pa. suffered a 20-year flood, its second in three years. After days of torrential rain, the borough’s former fire chief, who oversaw cleanup after Hurricane Ivan, described it as “one of the worst I’ve seen.” When it comes to the region’s tornadoes, which normally occur seasonally May through July, the potential for “tornadic events” now stretches almost year-round. The Pittsburgh warning area has seen more than triple its yearly average of tornadoes before July this year.

“So the weather is getting crazier,” McMullen says. “And it’s definitely something that we keep our eye on.” Ongoing climate studies have long shown warming temperatures, and NWS Pittsburgh has issued more heat-related alerts over the past decade.

“There’s probably a factor of that,” McMullen says, “But to what level, you can’t [say].”

They have a “common phrase” in the business, he explains: “Weather is your mood, climate is your personality.” Loosely interpreted, though there is a visible pattern of climate change, you can’t necessarily attribute a single, or even several, extreme weather events to it directly.

“One tornado in Western Pennsylvania in May or June or April or February does not mean climate change,” McMullen asserts. “It’s got to be prolonged … so that’s [important], to realize the scales of everything.”

When I visit the NWS Pittsburgh office, the city is still buzzing about tornadoes. But weather being infinitely changeable, predictions about a historic heat dome set to hover for days are pouring in. Storms, tornadoes, and “precip,” as the meteorologists call it, are temporarily in the rearview again.

Surrounding the office’s operations floor, which McMullen says is the smallest on the Eastern seaboard, are screens showing the Northeast’s predicted heat risk. As the seven-day forecast progresses, the color-coded counties in western Pennsylvania brighten from orange (moderate, category 2) to red to a frightening magenta (category 4, extreme).

“European’s got 600 decameter heights over Pa.!” McMullen declares, referring to a weather forecasting model measuring how much the heatwave could expand the atmosphere itself. Meteorologists call out other models’ predictions: 597 decameters, 598.5 — all rare to see on a weather map. They also use atmospheric pressure to forecast surface temperatures, clocking a run of days in the upper 90s.

Meteorologist Colton Milcarek sifts through climate data: the last time Pittsburgh logged five consecutive days above 95 degrees was 1994 (we ultimately didn’t break this record, but blew past some single-day highs).

“That’s hot!” McMullen says. “We try to find the most interesting model to talk about and we just shake our heads.”

Though they’re scientists, McMullen emphasizes that, as federal employees, they’re also public servants, quoting the NWS mission to protect life and property.

“People don’t realize heat is the number one killer in the country,” McMullen says. “It’s not lightning, it’s not tornadoes, it’s not flooding. It’s heat.”

Though Pittsburghers tend to have a “high weather IQ” with few weather fatalities in the region — which McMullen attributes in part to residents’ love of local TV news — safety is always of paramount concern.

Milcarek messages a Slack channel with media members, emergency managers, and other NWS partners about the upcoming heat risk. Communicating over Slack is much more efficient than earlier methods, says McMullen, who’s worked at NWS Pittsburgh for 15 years, allowing them to embed pictures and links and transmit essential information quickly.

“It’s just really important that we make the forecast and then communicate that message out to the public,” Milcarek tells CP. “Because even if we get some people to change their actions, potentially reschedule outdoor events, then that can be helpful … and keep people safe.”

The City of Pittsburgh, county governments, and other organizations all rely on NWS information to make decisions like whether to open cooling centers. The office also tracks a running list of events that might be affected by the weather: Pirates games, outdoor concerts and music festivals, motocross races.

The staff takes turns posting to NWS Pittsburgh’s social media, though McMullen makes a point of using yinz in his tweets “so people always know when I'm working.” On quiet, temperate days, he likes to focus on the positive and play up the nice weather.

On April 19, the NWS Pittsburgh Twitter account posted photos of the sunrise: “If you are up, hope yinz caught the sunrise! If you were still [sleeping emoji], no worries, I captured it here from our office n’at.”

Every meteorologist has their specialty — climate, hydrology, winter weather, severe weather, storm data — and these days, McMullen says, his is public outreach.

“I tell my kids I took one public speaking class in college and that’s all I do now,” McMullen laughs.

Meteorologists seem to know everyone has a formative weather experience, and McMullen’s memorized past events as public interest in climate has piqued. For Pittsburghers, that event might be the 1988 heatwave, the historic 1996 flood that jammed the Monongahela River with ice, or 2010’s Snowmageddon.

“Because that’s a question we get asked a lot,” McMullen says. “How was this compared to the norm?”

NWS always encourages thinking ahead, and CP’s visit is scheduled before McMullen leads an office tour for two families and 46 ham-radio operators, known to get information out during severe weather. He’s also preparing for a public weather spotting class at a library (part of NWS’s SKYWARN program) and a presentation at Nemacolin. After a tornado passed nearby, the resort in the Laurel Highlands asked NWS to conduct a tornado tabletop exercise walking through its emergency preparedness.

Lee Hendricks, a meteorologist and hydrologist who, at the time of our visit, was two weeks from retirement after nearly 40 years, marvels at the progression of weather technology. When he started in 1985, the office used floppy disks and ran on a Unix operating system. Hendricks remembers working during the 1996 flood and receiving readings from river gauges every four hours as Downtown Pittsburgh became inundated with water.

“The suspense would kill you,” he tells CP. “You were waiting for data … or you were busy dialing it up on a phone and entering data manually into the system. It wasn’t a great way of doing business.”

Now, NWS receives river readings every hour, which “has helped in leaps and bounds on being able to do this job.” Computer modeling has also progressed to where rainfall can be “reliably” predicted close to seven days out; when Hendricks started, it was 24 hours.

Meteorologist Chris Leonardi adds that machine learning and artificial intelligence have the potential to further evolve the science of forecasting.

I can’t help but ask the meteorologists about having god-like powers of prediction (or the illusion of them).

“Far from it!” says Leonardi. “We’re always trying to do our best and get it right. Sometimes we’re not going to, and we realize that, and realize that impacts a lot of people. We feel it when we don’t get it right ... [and] we sometimes take it very personally. So our goal is to always learn from everything.”

That said, “It’s fun,” Leonardi adds. “That’s why we're here. And it is kind of cool sometimes being in the know. I’m out getting a haircut and [someone says], ‘They’re saying we’re going to get six inches of snow.’ I’m like, how little do you know!”

“It's not so much a power, but it’s a feeling of importance,” Leonard says “It’s a feeling of inclusion, because everyone relates to the weather … It affects everybody. So you always feel like you’re part of the conversation. Everyone talks about the weather.”