The Pittsburgh Courier once dubbed Wylie Ave. in the Hill Distract as "the street that begins at a church and ends in jail." Indeed, as a new report confirms, for decades, Wylie Ave. was as much Black Pittsburgh's Main Street as it was an unjust pipeline to prison.

A recent article by the Equal Justice Initiative — an organization dedicated to ending mass icarceration — tells the story of an episode that unfolded in February 1909, when police rounded up more than 200 Black Pittsburghers and arrested them on spurious charges. Like much in Pittsburgh’s Black history, the 1909 events had been long forgotten. Many of the buildings on Wylie that bore witness to them have been torn down, replaced by vacant lots.

Even local historians were caught off guard by the EJI article. The story they tell took place 115 years ago, but it’s been echoed in recent years by familiar cycles of police violence and racial unrest.

Founded by lawyer Bryan Stevenson, the EJI is best known for its legal advocacy and educational efforts, including the widely acclaimed National Memorial for Peace and Justice (also known as the lynching memorial) in Montgomery, Ala. Its 1909 roundup story was one in a series of articles the organization has published.

“EJI produces a calendar that highlights examples of racial injustice throughout history,” a spokesperson emailed in response to questions about the story. “We researched the Pittsburgh narrative, and we’ve had it in our annual calendar for years.”

Mass hysteria fuels mass incarceration

The EJI piece highlights the story of Rial and Irene Lucas. The couple were living above Harrison’s Pool Hall at 1810 Wylie Ave. when they found themselves caught up in a wave of mass racial violence triggered by a white woman claiming that she had been assaulted.

Ida O’Neil was a white 20-year-old office worker whose scream the eve of Feb. 2, 1909, attracted the attention of a woman living nearby. She and another woman told police that they had seen a Black man running away from the Hill District scene.

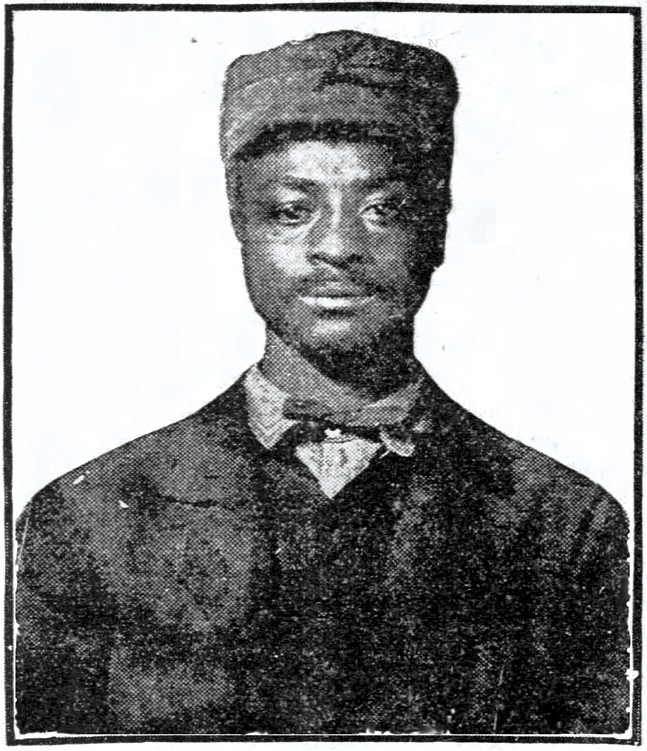

Within hours of the alleged event, O’Neil tentatively identified Mack McGee as the man who assaulted her. “That looks like him,” The Pittsburgh Press quoted O’Neil the next day. But she wasn’t sure.

McGee was among more than 100 Black men questioned in the hours after the alleged assault.

“All kinds and classes of men were up before the magistrate this morning,” wrote the Press on February 3, 1909. “Some were manifestly harmless and were quickly discharged. In the collection of 125 prisoners, however, there were some negroes who looked to be distinctly undesirable citizens.”

The men in the latter group, two-thirds of those picked up, were charged as “suspicious persons” and sent to the Allegheny County Jail downtown or the Allegheny County Workhouse near Blawnox.

McGee was one of the unlucky ones kept in custody. He was picked out of a police lineup by a white man who “chased” a Black man after another alleged assault on a different woman. The strongest evidence that police had against McGee: they’d recovered an old coat and a hat when they searched his Pasture Lane apartment.

O’Neil told the police that the man who attacked her wore a cap with “ribs” in it, the Pittsburgh Post reported. The paper added, “McGee wears a corduroy cap of that description.”

Though McGee ultimately was cleared of the alleged O’Neil assault, he nonetheless was fined $10 and sent to the Workhouse. It was his third (or fourth) trip there since 1905 — the others were for disorderly conduct and for being a “suspicious person.”

Under a Pittsburgh ordinance passed in 1867, anyone charged as a “suspicious person” in the city appeared before a police magistrate, who could unilaterally decide to summarily fine and imprison that person, no jury, no attorneys required.

After clearing McGee, the police then turned their attention to Lucas. By that point, newspapers around the nation had been publishing sensational articles beneath bold headlines reporting that police had rounded up between 200 and 1,000 Black Pittsburghers.

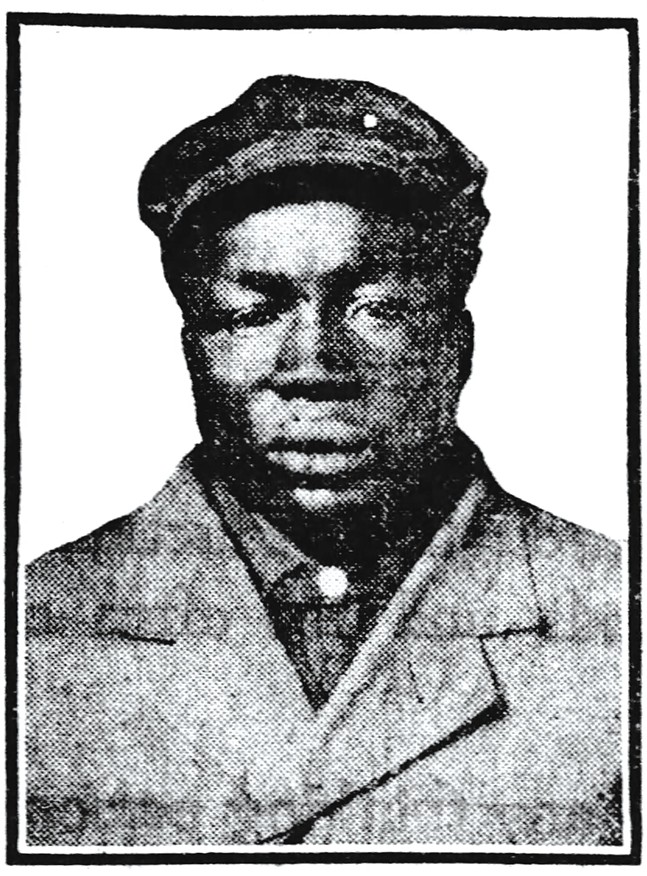

Rial Octavious Lucas was born in 1881 in Washington, D.C. Lucas attended public school there until he was 17. According to Pennsylvania penitentiary records, he was 5’4” and a moderate drinker. In Washington, he worked as a day laborer and was living with his mother and her second husband.

By 1906, Lucas and his sister Bertie were living on Wylie Ave. He was working as a janitor when he married domestic worker Irene Watson in 1907. Watson was born in 1886 in Delaware. In 1900, she was living with her widowed mother, two brothers and a sister in Philadelphia. Watson was 5’2”, and she attended public school until she was 12.

For reasons unknown — the original criminal case files are missing — police arrested the Lucases on Feb. 7, 1909. Less than two months after O’Neil’s alleged attack, a Pittsburgh jury, after deliberating for just 16 minutes, sentenced Rial Lucas to nine years in the Western Penitentiary on Pittsburgh's North Side. Newspapers described the charge against him as “assault”; the charge listed in his prison intake record was “rape.”

It took only two days for Irene Lucas to be arrested, prosecuted, and convicted as a “suspicious person.” She spent 30 days in the Allegheny County Workhouse — the maximum sentence for a first-time offender.

The road to remembering

The Courier’s clever Wylie Ave. motto was an apt metaphor for many Black residents and visitors who found themselves swept from the avenue’s nightclubs, pool halls, newsstands, and homes into a pipeline ending at the Allegheny County Jail. The two buildings at opposite ends of the street also are a stark visual reminder of how Pittsburgh remembers and commemorates white history while the city forgets and erases its Black history and landmarks.

Between the 1890s and 1950, racial violence erupted in communities throughout the United States. In 1898, dozens of Black residents were killed and Black elected officials were removed from office in Wilmington, N.C. White mobs went on a killing spree in Atlanta, Ga., in 1906 after newspapers published stories alleging assaults on white women. In the summer of 1919, more than two dozen communities experienced racial violence resulting in hundreds of Black deaths. Whites destroyed Tulsa, Okla.’s, Greenwood community — dubbed the Black Wall Street — in 1921. And, in 1923 a white mob rampaged through Rosewood, Fla., killing more than 30 people.

Those episodes don’t include more than 4,400 racial violence lynchings that the EJI has documented. A common thread running through many of these cases involves a white woman alleging that she had been assaulted or insulted by a Black man. Such breaches of segregation etiquette had one verdict, guilty, and a single sentence in Jim Crow’s vigilante court: death.

Despite making headlines around the nation as the events unfolded here in 1909, Pittsburgh histories are silent about the episode. Even local historians and university faculty members who have written many books about the Black experience here were taken by surprise when they read the EJI article.

“I was not aware of that episode,” Carnegie Mellon University history professor Joe William Trotter Jr. tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “I think that we just haven't done enough work, you know, to really uncover the many dimensions of the Black experience in the city over a long period of time.”

Laurence Glasco, who has taught history at the University of Pittsburgh since 1969, hadn’t known of the 1909 episode when the EJI contacted him as a source for their article.

“I was really stunned by it and fascinated to learn about it, because it goes against a lot of what we know about race and race relations in the Hill district historically,” Glasco explained.

Trotter connects the 2024 exposure of the 1909 episode to some of the reasons it has been forgotten or erased by historians.

“One of the things we have to keep in mind is that, very often, the research is driven about the politics of our times, right. I mean, it's almost inevitable,” he says.

Neither Trotter nor Glasco could definitively explain what kept the violent rhetoric in 1909 — calls for lynching — from leaping off newspaper front pages into the streets and deadly, destructive actions.

“It didn't break out into that — you don't have deaths coming out of this,” Trotter says. “We still have to say there was something about Pittsburgh that prevented that kind of violence from gaining ground.”

The historian speculated that officials prevented escalations in episodes like these by promising swift justice. “Even if the state sort of curtailed the violence, or helped to curtail the violence, it didn't totally exonerate the city from a pattern of racial hostility visited upon Black people.”

History repeats itself

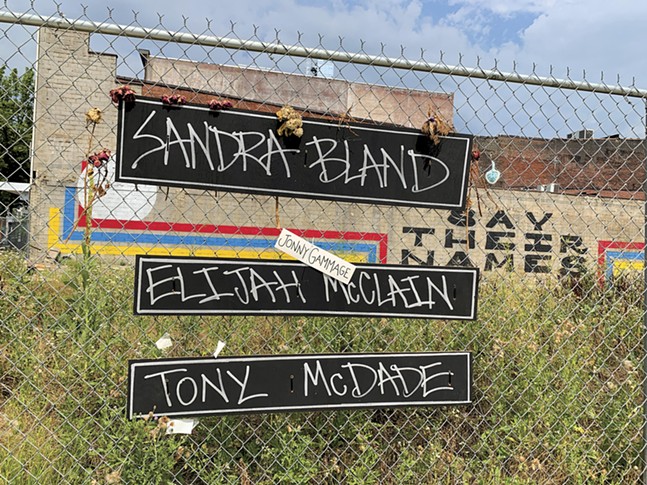

The actions by Pittsburgh police in 1909 resonate today. The pipeline to prison and police violence in Black communities are as close as daily headlines and social media timelines. Demonstrations against expanding the carceral state include the global protests in the wake of George Floyd’s 2020 murder in Minneapolis and the #StopCopCity movement that spread from Atlanta as activists try to prevent the construction of a massive police training facility.

The legacy of 1909’s excesses may be found in the deaths of Jonny Gammage in 1995, Antwon Rose in 2018, and Jim Rodgers in 2021. Local protests in the summer of 2020 yielded many complaints of police extremes.

Like much in Pittsburgh’s Black history, had it not been for EJI, Rial Lucas’s nine years in Western Penitentiary might have been forgotten and erased altogether. The prison itself, slated for demolition, is a painful and palpable monument to inequities in law enforcement and criminal justice.

“We don't want to keep something that has had a major negative impact on Black people and in our neighborhood,” Angel Gober, president of the Marshall-Shadeland Civic Group, told WESA last year.

In his 1984 memoir Brothers and Keepers, John Edgar Wideman, the award-winning Pittsburgh-born author, made the prison the setting for his brother’s incarceration and a central character.

“Western Penitentiary sprouts like a giant wart from the bare, flat stretches of concrete surrounding it,” Wideman wrote. To Wideman, Western Penitentiary punished its inmates and their loved ones by dehumanizing them.

Wideman’s take on the prison captures the sentiments held by Black Pittsburghers: revulsion, not nostalgia. Compare that to the efforts by white historic preservationists who sought to protect the landmark which in 2022 was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The conflicting views of the impending demolition underscore the need to better understand history holistically and equitably. They also speak to how Pittsburgh preserves its Black history landmarks: the jail at one end of Wylie Ave. is a tourist attraction with a brass plaque, and the church at the other end is condemned.

Thanks to efforts by EJI and new generations of local historians, sunlight is illuminating important stories from Pittsburgh’s past. These stories are important reminders that remembering the past is key to ensuring that we learn from past inequities and don’t repeat them in the future. It’s a lesson that is taking a long time to sink in.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled Bryan Stevenson's name. The error ha