The Blues Society — screening June 1-9 at the Harris Theater as part of the Three Rivers Arts Festival — attempts to understand that relationship and how one festival attempted to turn it into something beautiful and powerful.

The film, directed by Dr. Augusta Palmer, focuses on the Memphis Country Blues Festival, held in 1969 as a celebration of everything the blues had to offer, primarily shining a light on all-timers of the genre from the 1920s and 1930s, people who didn’t get their due in their time and were essentially relegated to obscurity by the time the festival was put on.

The film owes much to the director's late father, Robert Palmer, a noted music historian and author who attended the festival. The voice of actor Eric Roberts can be heard reading Robert Palmer's writings in the film.

The film charts a course that’s more than just a music documentary chronicling a single event. Described in the opening credits as a “moving image mixtape,” it’s instead a course charting of a moment and all the people who made it exist.

“I didn’t want to just make a concert film,” says Palmer in a press release. “I loved the arc of the story. The initial stake was guitarist Bill Barth’s baseball-size chunk of hash and guitarist Jim Dickinson’s $65 check from a Sun Studios session. It was white and Black musicians playing together during the height of the civil rights era. The KKK held a rally in that same public park a few days before. I wanted to understand what this moment meant to the people involved.”

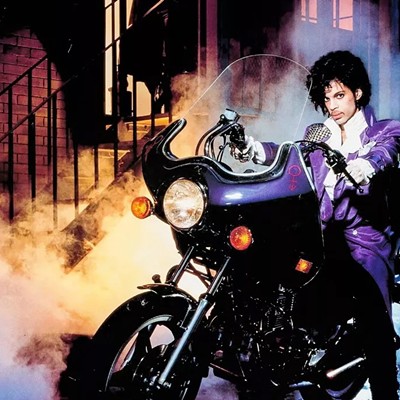

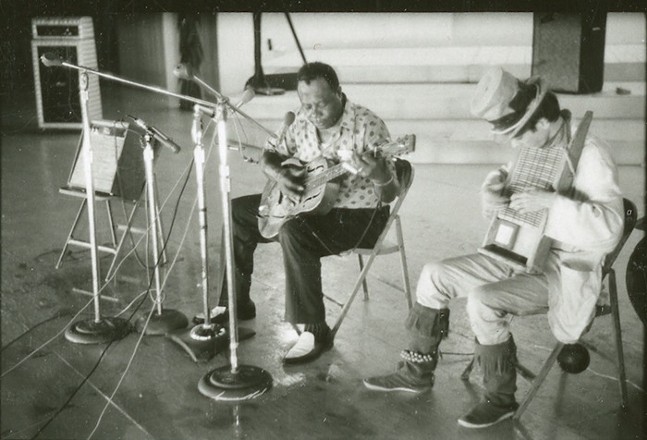

The Blues Society opens with Black and white artists playing together, gloriously grainy 1960s archival footage of a party in Memphis, sweaty artists from all walks of life cramming into a room to share what they love. It then pulls back to explore Memphis’ relationship to music, and how the city’s rich cultural tradition clashed with the inherent racism that kept blues music on the backburner.

“We all love the idea that music conquers all,” says Palmer. “Everyone can appreciate the blues music in this film, but love for this music didn’t cure white supremacy, and white blues fans were part of a power structure that took advantage of Black artists. I love the enthusiasm of that white hippy idealism, but the rules were much more stringent back then. There were segregated bathrooms for employees at the bandshell. Racial inequality has become more and more clear to the nation since the pandemic. We’ve come a long way, but still have a long way to go.”

Blues masters like Furry Lewis, Nathan Beauregard, and Rev. Robert Wilkins joined with East Village counterculture members like Bill Barth, a musician and historian who saw an opportunity to showcase these artists in the light that they deserved, often walking around Memphis door-to-door asking to buy records or play with the greats. And there were newer artists like Rufus Thomas and Johnny Winter, whose music was forever indebted to the sounds and styles of the blues that came before them.

They all came together at the Memphis Country Blues Festival, a three-day event as celebrated as it was protested. Newspapers and politicians at the time spoke out in favor of it yet it was protested and pilloried by many of the Southerners who never accepted the blues or the people who created it. Due to the obscurity of the festival, Palmer says she approached the documentary by "putting it together like a collage,” adding material as she discovered it.

“There’s stuff in the film I didn’t even find until last year," she explains. "I had this bootleg tape that someone had labeled ‘1969,’ but when I had the tape transferred we found that it was actually from 1966! So we suddenly had media to work with from that first festival."

Palmer says the primary text featured in the film, written by her father, was from an article not discovered until late in the filmmaking process. "The film and I both benefited from having that time to think about what I wanted to say.”

What Palmer delivers is a fascinating time capsule about a seldom-discussed event, and provides insight into a music industry that doesn’t always accept the people inside it.

The Blues Society. 5:30 p.m. Sat., June 1-Sun., June 9. Harris Theater. 809 Liberty Ave., Downtown. Free. traf.trustarts.org