Through research, Newman found that Union members historically voted as bloc, supporting the Democratic Party and its candidates. But after exhaustive research and interviews in counties from Erie to Somerset, she found that blue-collar workers’ voting tendencies have changed.

“I had this idea of trying to figure out what happened in Western Pennsylvania,” Newman tells Pittsburgh City Paper. “I was looking at some of the voting trends and how everything has gotten, outside of [Pittsburgh], more Republican in the past 30 years or so.”

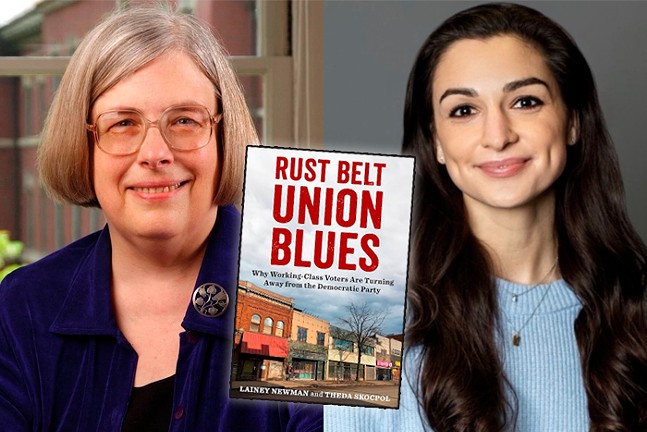

Newman and her thesis advisor, Theda Skocpol, co-authored Rust Belt Union Blues: Why Working-Class Voters are Turning Away from the Democratic Party (Columbia University Press). The two women will appear on Sat., March 9 at White Whale Bookstore in Bloomfield, and on Sun., March 10 as guests of of a sold-out event, organized by the Battle of Homestead Foundation, at the First Unitarian Church in Shadyside.

Newman and Skocpul conducted numerous interviews with union members, many of them retired. The central point of the Rust Belt Union Blues, they write, is that union members of the mid-20th century were not a “disaggregated bunch of (white male) lone wolves, but rather a dense social web of interconnected workers, family members, and neighbors that included grounded union and political organizations along with other community groups.”

Newman was curious about the community roles unions played, and “how that has all but vanished.” She found that union halls provided a meeting place not only to organize but to commune and foster relationships.

“Particularly with unions, what’s lost when we don’t have these types of local organizations is the ability for people to come together as community members, for one,” Newman says. “But then also receive signaling and messaging about various political and social topics that unions sort of used to guide views on, and present an alternative perspective from what was being talked about in conservative circles. Unions used to provide a counterweight that is largely not there anymore.”

While unions fostered brotherhood and community, some groups were not welcomed. Newman and Skocpul write that, in 1960, the majority of American unions had either no female membership or under 10% female membership. Non-white members also were few, often less than 10%, between 1960-1968.

“Unions, like almost every other institution in the country, definitely had histories of discrimination and prejudice,” Newman says. “That being said, they were out in front of the issues on the national level. And in terms of other types of civic organizations, unions in many places were ahead of other similar civic organizations that were lagging behind … In general, [unions] were a force for community cohesion.”

The diminution of unions and their meeting spaces is not unique. Other social organizations, from fraternal orders such as Lions Clubs International and the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks to Veterans of Foreign clubs, also have lost membership. Instead of gathering in person, people are more likely to congregate online with those of similar inclinations and viewpoints.

“In these places that used to exist in person, people would come together and there would be natural sort of difference of opinions presented,” Newman says. “And now we’re all sort of in these silos.”

But when people do gather, the authors found an unanticipated meeting place: gun clubs.

“People were bringing them up, mentioning going to the shooting range with friends, seeing union retirees. and spending more time there socially at the clubhouse of the ranges,” Newman says. “I think that’s a forum, where people are getting together in the political and social backdrop that those places have. And it’s important because all those places we looked at were NRA affiliated and that’s obviously a very political organization as opposed to people coming together for drinks at a union hall or VFW, where there’s a different messaging coming from the organization itself.”

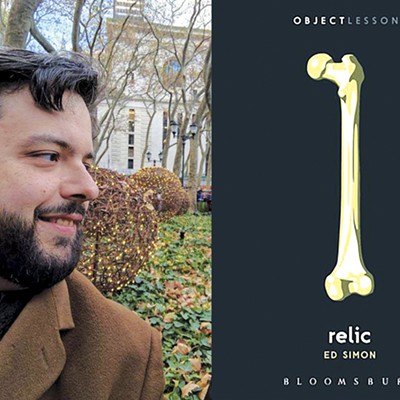

Reading & Conversation: Lainey Newman and Theda Skocpol of Rust Belt Union Blues with Ed Simon. 7 p.m. Sat., March 9. White Whale Bookstore. 4754 Liberty Ave., Bloomfield. Free. RSVP required. whitewhalebookstore.com/events