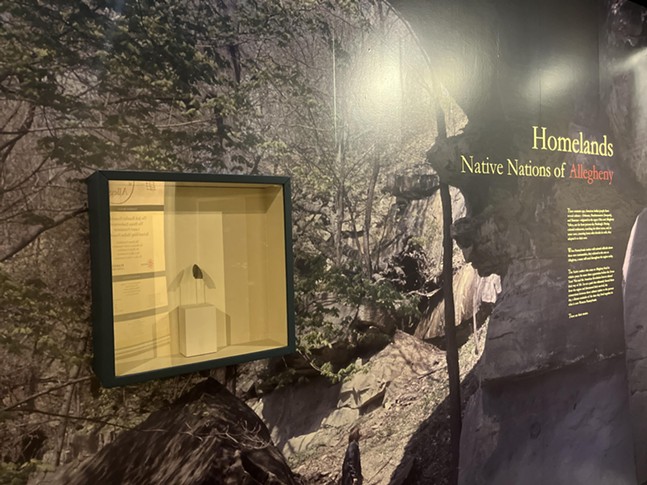

The Senator John Heinz History Center, which operates the Fort Pitt Museum and Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Avella, assembled the temporary exhibit through thoughtful collaboration with members of federally recognized tribes belonging to the Six Nations of Haudenosaunee (hoh-din-oh-SHOW-nee). It includes carefully displayed artifacts on loan from Indigenous people and curated from the History Center’s collections, as well as maps, prints, photos, and contemporary artworks that trace the history of Allegheny as it was and is today.

Shideezhi’ Emarthla (pronounced sha-DAY-zha), a member of the Seneca-Cayuga Nation who worked with the Fort Pitt Museum to plan and assemble the exhibit, says the work has helped her rediscover and reclaim her roots in the area. She credits the staff for working with Indigenous people from the inception of Homelands.

“With my time being here working as an educator, it really has opened my eyes to the idea — not even with children, but also the grown adults — that do not understand that native tribes that called this area home, we're still in existence to this day,” Emarthla tells Pittsburgh City Paper.

Western Pennsylvania was settled millennia ago by people who left artifacts including the Miller Point, a 14,000-year-old arrowhead that’s displayed at the beginnings of Homelands. However, many of these groups had disappeared or been wiped out by disease by the time of colonization. Subsequently, Haudenosaunee Indians (also known as the Iroquois, a term with pejorative origins), including members of the Seneca Cayuga, Delaware, Seneca tribes, as well as the Shawnee, moved into what is now Western Pennsylvania almost exactly 300 years ago as they fled encroaching colonial settlements. Here, they found an abundant land of old-growth forests sparsely populated by French fur trappers.

The tribes quickly established settlements along the Ohi:yo’, or Beautiful River, that stretched from Upstate New York to what’s now Illinois — for the Seneca, the Allegheny and Ohio rivers were a single entity. Here, they conducted trade with the French and among one another, with some Indigenous settlements built right next to French forts.

Artifacts from this time visitors will see at Homelands include handmade weapons, a pipe-tomahawk forged by a local craftsman, a hand-carved spoon on loan from the Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural Center, and ceremonial clothing.

For a generation, Allegheny prospered. However, wars and broken promises by the fledgling United States led to genocide and suppression of Indigenous culture that is only recently being addressed. Most of the people whose ancestors lived here, including Emarthla’s, fled or were forcibly resettled. This period in Allegheny is marked by a literal corner-turn in the exhibit that makes tangible the shift from cautious cooperation to distrust and a seemingly endless string of broken treaties between the U.S. and different Indigenous peoples, as depicted in a Robert Griffing painting displayed on the far wall.

However, those cultures weren’t extinguished, and different Haudenosaunee tribes have continued to intermarry and support one another during ceremonies and celebrations. This contemporary phase of rediscovery and regrowth is commemorated by photos and striking traditional textiles made more recently — a testament to the continued legacy of Allegheny.

“This relationship that was being formed [in Allegheny in the 18th century] is actually a relationship that still exists to this very day back in Oklahoma,” Emarthla says.

Homelands serves in part as a commemoration of what was lost but also a rebuilding of trust among those who were hesitant to return, including D.J. Huff, a member of the Seneca Nation, who notes that the Seneca had a presence in Pennsylvania within living memory of older Pittsburghers.

“The1960s was a pretty pivotal time for the Seneca people,” Huff told local media during a preview of Homelands. “In 1965, the Kinzua Dam opened up just upriver to help flood control, they say, for the city of Pittsburgh.” The dam submerged much of the Seneca homeland beneath the Allegheny Reservoir in a final violation of the Treaty of Canandaigua, while a nearby highway sliced what remained of the reservation in New York state in half.

“Two-thirds of our elders passed away within … three and five years of the Kinzua Dam being put there,” Huff said.

Huff and Emarthla both said many of their elders have long felt unwelcome in the North — this, Huff pointed out, despite Native Americans’ disproportionate service in the military, often spurred by a strong connection to their homeland. Meanwhile, Haudenosaunee with family in Canada periodically suffered indignities including restricted travel across the arbitrary lines breaking their traditional homeland into pieces. Emarthla and Huff say expanded travel rights and projects such as Homelands are helping change that, although many Seneca Cayuga elders now view Oklahoma as their home.

“To be honest with you, I don't think they'll ever move here,” Emarthla tells CP. “But I think there'll start being more of an ideal of traveling here.”

Regardless of geography, Emarthla says many Native Americans are reconnecting with their culture through events, longhouse etiquette classes, and dances. Huff similarly said competency in native languages is “at an all-time high” from what it had been at the end of last century — in spite of still-recent wounds like the Kinzua Dam.

“Even though that was a black mark in our history,” he said, “it's also a springboard to rejuvenate cultural preservation.”

The exhibit will remain on view through 2025. Also planned is cultural programming, including an Aug. 17-18 stickball demonstration (the sport is a forerunner of the modern game of lacrosse). Though Homelands only occupies about a quarter of the museum’s square footage, Emartha, who will remain on staff through the duration of the exhibit, sees it as an important starting point and hopes the Fort Pitt Museum will continue to center the Indigenous experience in some way.

“It is a good point where I hope that, when I leave, somebody can take my position where they can learn just as much,” Emarthla tells CP. “For me, working here is a beginning.”