Bestselling author Abraham Verghese talks family, writing, and drowning

[

{

"name": "Local Action Unit",

"component": "24929589",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

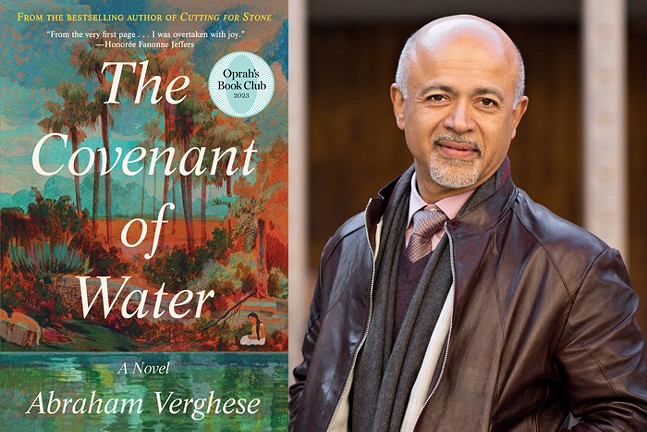

Abraham Verghese produced a voluminous novel — over 700 pages — that never feels bloated or long. Set in Kerala on India’s Malabar Coast, The Covenant of Water follows a family haunted by a weird condition — in every generation, someone drowns. The two central characters — a girl who marries at 12 and eventually becomes Big Ammachi, the family matriarch, and Digby, a physician unable to find suitable work in Glasgow because he is Catholic — set out on unlikely paths that eventually converge.

Verghese's first novel, Cutting for Stone, sold over 1.5 million copies and spent more than 100 weeks on the New York Times bestsellers list. The Covenant of Water has, since its summer release, garnered praise for its epic scale, with one NYT review calling it "grand, spectacular, sweeping and utterly absorbing."

Verghese, a professor at Stanford University School of Medicine and National Humanities Medal winner, will appear Mon., Nov. 13 as a guest of the Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures Ten Evenings series.

Pittsbrugh City Paper spoke with Verghese about the challenges of writing an expansive, multi-generational story, how his medical background informed the plot, and how his late mother influenced the book.

One of the themes in The Covenant of Water seems to be how Western religion mixes with the mysticism of that region of India. We often see Big Ammachi talking directly to God and, in one instance, she hears him speaking to her. She also talks to the ghost of her husband’s first wife.

Did you want to explore this mix of spirituality in the region? Did it provide the moral underpinning for the story you wrote?

AV: To be honest, I’m not that intentional. I wasn’t exploring abstract themes (nor was I proselytizing). My goal is always a good story well told, and for that, I was trying to accurately portray the palpable faith of the St. Thomas Christians of that era, people like both my grandmothers. For them, God and religion got them through life. They lived partly in the material world and quite substantially in the realm of what isn’t seen but was just as real to them. Both women were inspiring and quietly heroic. Each of them lost an adolescent son — one to typhoid and another to rabies — yet they soldiered on. The world abounds with such heroic figures.

Even my parents, who taught in school and college in Ethiopia and the U.S., have an unquestioning faith that I envy. My mother, alas, didn’t live to see the book come out, but her anecdotes of her childhood were an inspiration. She was the source of so many of the anecdotes. She was excited that I was writing The Covenant of Water. She died at 93.

Recently, I said to my 96-year-old father, speaking of the extraordinary reception of my novel, “Perhaps Mom had a hand in this. She’s watching over me.” I think he didn’t like my whimsical tone because he said indignantly, “Of course she is!” He had no doubts. The cross of our generation may be to be incapable and too questioning of such faith.

Continuing with the spiritual theme, we learn of the origin of the title midway through the novel: "Yes, old man, yes, eyes open to this precious land and its people to the covenant of water that washes away the sins of the world."

Can you talk about how you came up with the title? Did it emerge during the writing of the novel? Was it something you had in mind when you started?

AV: We came to the title quite late. I think titles should be a bit mysterious. Each reader arrives at their interpretation of its meaning, perhaps before it is overtly stated as in the quote you used. I don’t have the key.

What I mean by that is I believe a novel is truly a collaborative venture: the writer provides the words and the reader the imagination so that the reader’s brain creates a mental "movie," a fictional dream unique to that reader.

That said, for me the word “Covenant” had a lovely Old Testament ring to it. As for “water,” that is obvious because the setting is Kerala, and because the fictional family has issues with water.

But water is life, isn’t it? We exist in a watery womb for nine months before we emerge; our bodies are two-thirds water; and we use water in rituals of faith as in baptism to the Christian tradition, or the priest washing the feet of the faithful recapitulating Christ washing his disciples’ feet. All the above is just my attempt at an explanation that I wouldn’t want to impose on the reader. Each reader decides, and they are right.

The theme of water — being fearful of water, the "Condition” in the family Big Ammachi marries into, the monsoons that ultimately arrive — is constantly present in the novel.

Did you want to explore the dichotomy of how water is essential to life, but also is a dangerous force?

AV: The most premeditated decision I made with this novel was to set it in Kerala. Geography is character, and since Kerala is a coastal strip of territory with so many rivers, ponds, canals, backwaters, and lakes, it gives it a distinct character. In Kerala water is the great connector, the highway, the circulatory system that connects everyone; the monsoon is the beating heart.

Water also connects people in one period with another. I raised the stakes for the family by giving one or more members in each generation a disorder that would give afflicted members an aversion to water, and a propensity to drown. As a long-time teacher of medicine, I keep a lot of rare diseases “in my back pocket,” so to speak, ready to bring it out as a riddle or question in a dull moment. The disease (called the “Condition” in the novel) is one such rare entity.

Digby seems to be a curious character — initially, I couldn’t imagine how he would fit into the story. But gradually, he becomes important to the plot.

Can you talk about how he emerged when you were writing the novel? Were there a lot of doctors like him — outcasts, for whatever reasons — who ended up in India because it was difficult to practice elsewhere?

AV: If one is writing a sweeping novel about 1900-1970 in India, it would be hard to do so without characters who were Western. The Indian Medical Service (IMS) was created and run entirely by the British who founded the first Western-style (or allopathic) schools. The professors at these schools (including Madras Medical College where I studied) were at one time all British.

Of the colonists, a good percentage were Scottish. They came out for their own reasons, some perhaps because they were outcasts, or for the adventure. By the time I was in medical school, they were long gone, but their system of education remains strong, comically strong, at times, in the many arcane and archaic rituals that are still preserved.

Similarly, the individuals who first carved out and developed vast estates on the slopes of the Western Ghats were expatriates of many nationalities, not just British.

The arc of the story — how it plays out, the eight decades over which it occurs — is, at times, breathtaking. What was writing The Covenant of Water like for you? Were you going back and forth between chapters trying to cohesively tie the plots, subplots, and character histories together?

AV: I wish I was the sort of writer who knows the whole plot before starting. ... I began with trying to imagine the young bride and her trials. It grew from there quite organically, but also with many blind alleys, months of writing pages that may be good, but you realize later don’t advance the story. There was a moment two-thirds of the way into the book where I could see the way ahead; I could see how things will come together. So, at that point, I have arrived at the same place as writers who have the plot worked out before they begin.

My way is much less efficient. I should also say that few people understand the critical role of an editor. I believe, just like with movies, the editor should be named on the title page. As a writer, I have no objectivity. I need someone I trust, someone with skill, discernment, and confidence to shape and cut, and who ideally is sensitive to one’s ego. With all four of my books, I have had gifted editors; with Covenant, Peter Blackstock at [Grove Atlantic] was brilliant in giving it its final shape. I consulted with Courtney Hodell before that.

I read novels where I sense the absence of an editor. My sense is that, in modern publishing, an old-fashioned editor in the mold of Maxwell Perkins is rare, and writers are expected to deliver a finished jewel. I was blessed with Peter.

The sentence you wrote, "As long as I have my eyes, then novels, the great lies that tell the truth, the world in its most heroic and salacious forms can always be mine" is one of the best descriptions of what it’s like to read fiction. Can you talk about what fiction means to you? Is it just as essential to your life as the practice of medicine?

AV: I believe I am paraphrasing Camus and Dorothy Allison. Though if you look it up it is often falsely ascribed to me, which tells you how much I love the idea. It encapsulates why fiction resonates with us — because it has some fundamental truth we recognize. A good novel should instruct us and stay with us forever, like a lived experience.

Proust said that a reader uses the novel as an “optical instrument” to read himself or herself. I puzzle over the fact that we use stories to raise our children; their worlds expand through a series of instructional stories ... and then as adults — and this is true, especially of men, especially of professional colleagues — many consider themselves too “serious” to be reading novels. Serious people should read biographies and non-fiction is the implication. When you don’t read fiction, a creative part of your brain atrophies, the part that relishes taking words on a page and using your imagination to make a mental movie. That’s my medical opinion!

So yes, reading fiction is essential to my life. Writing fiction is a bit of a luxury. And it is hard. With both my novels, when I was done I had the feeling of having put every single thing I knew in there and the tank was empty. It’s a good feeling. I’ll always write because it is how I process the world and my scattered mind.

But I feel no compulsion to start a new novel unless I am moved to do so. As a society, we get too easily locked into the notion that if you succeed in anything you must keep doing it and top it. Of course, I have the luxury to say this because I have a fulfilling day job at Stanford and a profession that I love.

Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures presents Abraham Verghese. 7:30 p.m. Mon., Nov. 13. Online tickets $18. pittsburghlectures.org

Verghese's first novel, Cutting for Stone, sold over 1.5 million copies and spent more than 100 weeks on the New York Times bestsellers list. The Covenant of Water has, since its summer release, garnered praise for its epic scale, with one NYT review calling it "grand, spectacular, sweeping and utterly absorbing."

Verghese, a professor at Stanford University School of Medicine and National Humanities Medal winner, will appear Mon., Nov. 13 as a guest of the Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures Ten Evenings series.

Pittsbrugh City Paper spoke with Verghese about the challenges of writing an expansive, multi-generational story, how his medical background informed the plot, and how his late mother influenced the book.

One of the themes in The Covenant of Water seems to be how Western religion mixes with the mysticism of that region of India. We often see Big Ammachi talking directly to God and, in one instance, she hears him speaking to her. She also talks to the ghost of her husband’s first wife.

Did you want to explore this mix of spirituality in the region? Did it provide the moral underpinning for the story you wrote?

AV: To be honest, I’m not that intentional. I wasn’t exploring abstract themes (nor was I proselytizing). My goal is always a good story well told, and for that, I was trying to accurately portray the palpable faith of the St. Thomas Christians of that era, people like both my grandmothers. For them, God and religion got them through life. They lived partly in the material world and quite substantially in the realm of what isn’t seen but was just as real to them. Both women were inspiring and quietly heroic. Each of them lost an adolescent son — one to typhoid and another to rabies — yet they soldiered on. The world abounds with such heroic figures.

Even my parents, who taught in school and college in Ethiopia and the U.S., have an unquestioning faith that I envy. My mother, alas, didn’t live to see the book come out, but her anecdotes of her childhood were an inspiration. She was the source of so many of the anecdotes. She was excited that I was writing The Covenant of Water. She died at 93.

Recently, I said to my 96-year-old father, speaking of the extraordinary reception of my novel, “Perhaps Mom had a hand in this. She’s watching over me.” I think he didn’t like my whimsical tone because he said indignantly, “Of course she is!” He had no doubts. The cross of our generation may be to be incapable and too questioning of such faith.

Continuing with the spiritual theme, we learn of the origin of the title midway through the novel: "Yes, old man, yes, eyes open to this precious land and its people to the covenant of water that washes away the sins of the world."

Can you talk about how you came up with the title? Did it emerge during the writing of the novel? Was it something you had in mind when you started?

AV: We came to the title quite late. I think titles should be a bit mysterious. Each reader arrives at their interpretation of its meaning, perhaps before it is overtly stated as in the quote you used. I don’t have the key.

What I mean by that is I believe a novel is truly a collaborative venture: the writer provides the words and the reader the imagination so that the reader’s brain creates a mental "movie," a fictional dream unique to that reader.

That said, for me the word “Covenant” had a lovely Old Testament ring to it. As for “water,” that is obvious because the setting is Kerala, and because the fictional family has issues with water.

But water is life, isn’t it? We exist in a watery womb for nine months before we emerge; our bodies are two-thirds water; and we use water in rituals of faith as in baptism to the Christian tradition, or the priest washing the feet of the faithful recapitulating Christ washing his disciples’ feet. All the above is just my attempt at an explanation that I wouldn’t want to impose on the reader. Each reader decides, and they are right.

The theme of water — being fearful of water, the "Condition” in the family Big Ammachi marries into, the monsoons that ultimately arrive — is constantly present in the novel.

Did you want to explore the dichotomy of how water is essential to life, but also is a dangerous force?

AV: The most premeditated decision I made with this novel was to set it in Kerala. Geography is character, and since Kerala is a coastal strip of territory with so many rivers, ponds, canals, backwaters, and lakes, it gives it a distinct character. In Kerala water is the great connector, the highway, the circulatory system that connects everyone; the monsoon is the beating heart.

Water also connects people in one period with another. I raised the stakes for the family by giving one or more members in each generation a disorder that would give afflicted members an aversion to water, and a propensity to drown. As a long-time teacher of medicine, I keep a lot of rare diseases “in my back pocket,” so to speak, ready to bring it out as a riddle or question in a dull moment. The disease (called the “Condition” in the novel) is one such rare entity.

Digby seems to be a curious character — initially, I couldn’t imagine how he would fit into the story. But gradually, he becomes important to the plot.

Can you talk about how he emerged when you were writing the novel? Were there a lot of doctors like him — outcasts, for whatever reasons — who ended up in India because it was difficult to practice elsewhere?

AV: If one is writing a sweeping novel about 1900-1970 in India, it would be hard to do so without characters who were Western. The Indian Medical Service (IMS) was created and run entirely by the British who founded the first Western-style (or allopathic) schools. The professors at these schools (including Madras Medical College where I studied) were at one time all British.

Of the colonists, a good percentage were Scottish. They came out for their own reasons, some perhaps because they were outcasts, or for the adventure. By the time I was in medical school, they were long gone, but their system of education remains strong, comically strong, at times, in the many arcane and archaic rituals that are still preserved.

Similarly, the individuals who first carved out and developed vast estates on the slopes of the Western Ghats were expatriates of many nationalities, not just British.

The arc of the story — how it plays out, the eight decades over which it occurs — is, at times, breathtaking. What was writing The Covenant of Water like for you? Were you going back and forth between chapters trying to cohesively tie the plots, subplots, and character histories together?

AV: I wish I was the sort of writer who knows the whole plot before starting. ... I began with trying to imagine the young bride and her trials. It grew from there quite organically, but also with many blind alleys, months of writing pages that may be good, but you realize later don’t advance the story. There was a moment two-thirds of the way into the book where I could see the way ahead; I could see how things will come together. So, at that point, I have arrived at the same place as writers who have the plot worked out before they begin.

My way is much less efficient. I should also say that few people understand the critical role of an editor. I believe, just like with movies, the editor should be named on the title page. As a writer, I have no objectivity. I need someone I trust, someone with skill, discernment, and confidence to shape and cut, and who ideally is sensitive to one’s ego. With all four of my books, I have had gifted editors; with Covenant, Peter Blackstock at [Grove Atlantic] was brilliant in giving it its final shape. I consulted with Courtney Hodell before that.

I read novels where I sense the absence of an editor. My sense is that, in modern publishing, an old-fashioned editor in the mold of Maxwell Perkins is rare, and writers are expected to deliver a finished jewel. I was blessed with Peter.

The sentence you wrote, "As long as I have my eyes, then novels, the great lies that tell the truth, the world in its most heroic and salacious forms can always be mine" is one of the best descriptions of what it’s like to read fiction. Can you talk about what fiction means to you? Is it just as essential to your life as the practice of medicine?

AV: I believe I am paraphrasing Camus and Dorothy Allison. Though if you look it up it is often falsely ascribed to me, which tells you how much I love the idea. It encapsulates why fiction resonates with us — because it has some fundamental truth we recognize. A good novel should instruct us and stay with us forever, like a lived experience.

Proust said that a reader uses the novel as an “optical instrument” to read himself or herself. I puzzle over the fact that we use stories to raise our children; their worlds expand through a series of instructional stories ... and then as adults — and this is true, especially of men, especially of professional colleagues — many consider themselves too “serious” to be reading novels. Serious people should read biographies and non-fiction is the implication. When you don’t read fiction, a creative part of your brain atrophies, the part that relishes taking words on a page and using your imagination to make a mental movie. That’s my medical opinion!

So yes, reading fiction is essential to my life. Writing fiction is a bit of a luxury. And it is hard. With both my novels, when I was done I had the feeling of having put every single thing I knew in there and the tank was empty. It’s a good feeling. I’ll always write because it is how I process the world and my scattered mind.

But I feel no compulsion to start a new novel unless I am moved to do so. As a society, we get too easily locked into the notion that if you succeed in anything you must keep doing it and top it. Of course, I have the luxury to say this because I have a fulfilling day job at Stanford and a profession that I love.

Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures presents Abraham Verghese. 7:30 p.m. Mon., Nov. 13. Online tickets $18. pittsburghlectures.org