31 Days of the Undead: Plan 9 from Outer Space and the Unexpected Legacy of Ed Wood

[

{

"name": "Local Action Unit",

"component": "24929589",

"insertPoint": "3",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

}

]

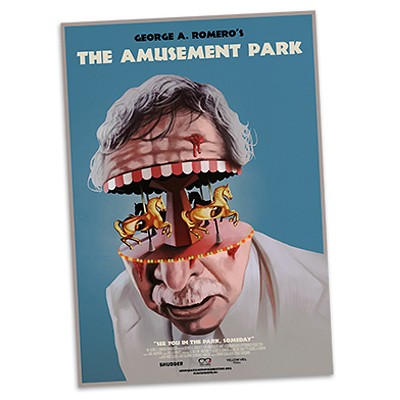

In honor of Romero Lives!, the city's month-long George A. Romero tribute, Pittsburgh City Paper presents 31 Days of the Undead, a series of reviews and essays about zombie media. Look for new posts going up every day from now through Oct. 31.

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959)

The late George A. Romero is credited for making zombies mainstream, paving the way for generations of filmmakers and authors to continuously reinvent the figure to suit their own creative needs. But Romero didn’t exist in a vacuum and while he and his scrappy Pittsburgh crew may have struck a major chord back in 1968, others had already tried their hand at co-opting a legend with roots going back to the folklore of West Africa.

I considered this recently while watching a live-score performance of the sci-fi B-movie classic, Plan 9 from Outer Space, presented by the musician Swampwalk and local pop-art company Alternate Histories. Released nearly 10 years before Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead, the 1959 work by underground director Ed Wood earned a reputation as the worst movie ever made (in all fairness, it has definitely lost that title in a time when Troll 2, The Room, and Birdemic exist).

Though I had seen the film before, and even performed a live read of it, I completely forgot that the titular plot device, Plan 9, involves aliens coming to Earth and raising the dead with ray guns. In being re-introduced to this, I was struck by the concept that the deceased being resurrected was supposed to be normal, everyday people with families and loved ones.

This deviates from previous, inarguably racist and xenophobic depictions of zombies, as is the case with White Zombie, a 1932 release considered to be the first feature-length zombie horror film ever made. In it, iconic Dracula actor Bela Lugosi – for whom Plan 9 would become his final film, as he died during production – plays a voodoo master in Haiti who uses coded Black voodoo powers to terrorize young white women. I Walked with a Zombie (1943) by Jacques Tourneur was less subtle, as a white, unconscious woman being carried off by a dead-eyed Black zombie became the defining image from the film.

But Wood never relies on the voodoo trope, instead completely separating the zombie from its origins and retooling it as part of a nonsensical plan to stop humans from inventing a bomb capable of destroying the galaxy. There’s no “black magic” or witch doctors – just a few snobby aliens playing with dead bodies for reasons known only to them.

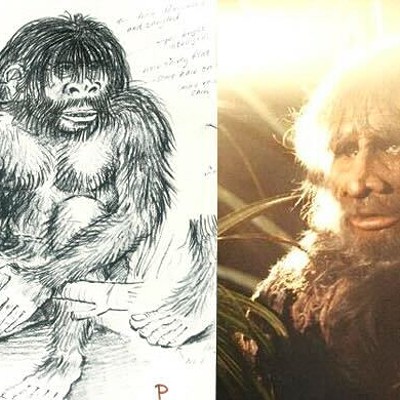

That the risen were supposed to be normal American people – an old married couple and police detective – also distinguishes it in a sub-genre then defined by exotic island locales, glamorous women, and threatening non-white and, in Lugosi's case, European Others. Never mind that Wood's “normal American people” were played by the colossally odd-looking, barely coherent Tor Johnson, Lugosi in his signature Dracula cape, for some reason, and the youthful, wasp-waisted goth-alien Vampira unconvincingly portraying an elderly deceased housewife.

And yet it’s from here, it seems, that Romero took the torch and sprinted off. Unlike Wood, who depended on his stable of kooky actor friends and a sad, aged Lugosi, Romero actually did employ regular people to portray zombies in his Living Dead series – many older native Pittsburghers will relate how their family members, friends, or co-workers were among the undead horde encroaching on the farmhouse in Night or on the Monroeville Mall in Dawn of the Dead.

As observed by many film critics and historians, this is likely what made Romero’s Living Dead films resonate with so many people, the indiscriminate notion that anyone could fall victim to zombification. That Romero also cast strong Black and female leads in these films further evolved them from their predecessors.

Romero, as far as I can tell, never credits Wood with influencing him. Even so, I can’t help but think that Wood, who was often mocked and dismissed for his off-beat choices, walked so Romero and others could run.

Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959)

The late George A. Romero is credited for making zombies mainstream, paving the way for generations of filmmakers and authors to continuously reinvent the figure to suit their own creative needs. But Romero didn’t exist in a vacuum and while he and his scrappy Pittsburgh crew may have struck a major chord back in 1968, others had already tried their hand at co-opting a legend with roots going back to the folklore of West Africa.

I considered this recently while watching a live-score performance of the sci-fi B-movie classic, Plan 9 from Outer Space, presented by the musician Swampwalk and local pop-art company Alternate Histories. Released nearly 10 years before Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead, the 1959 work by underground director Ed Wood earned a reputation as the worst movie ever made (in all fairness, it has definitely lost that title in a time when Troll 2, The Room, and Birdemic exist).

Though I had seen the film before, and even performed a live read of it, I completely forgot that the titular plot device, Plan 9, involves aliens coming to Earth and raising the dead with ray guns. In being re-introduced to this, I was struck by the concept that the deceased being resurrected was supposed to be normal, everyday people with families and loved ones.

This deviates from previous, inarguably racist and xenophobic depictions of zombies, as is the case with White Zombie, a 1932 release considered to be the first feature-length zombie horror film ever made. In it, iconic Dracula actor Bela Lugosi – for whom Plan 9 would become his final film, as he died during production – plays a voodoo master in Haiti who uses coded Black voodoo powers to terrorize young white women. I Walked with a Zombie (1943) by Jacques Tourneur was less subtle, as a white, unconscious woman being carried off by a dead-eyed Black zombie became the defining image from the film.

But Wood never relies on the voodoo trope, instead completely separating the zombie from its origins and retooling it as part of a nonsensical plan to stop humans from inventing a bomb capable of destroying the galaxy. There’s no “black magic” or witch doctors – just a few snobby aliens playing with dead bodies for reasons known only to them.

That the risen were supposed to be normal American people – an old married couple and police detective – also distinguishes it in a sub-genre then defined by exotic island locales, glamorous women, and threatening non-white and, in Lugosi's case, European Others. Never mind that Wood's “normal American people” were played by the colossally odd-looking, barely coherent Tor Johnson, Lugosi in his signature Dracula cape, for some reason, and the youthful, wasp-waisted goth-alien Vampira unconvincingly portraying an elderly deceased housewife.

And yet it’s from here, it seems, that Romero took the torch and sprinted off. Unlike Wood, who depended on his stable of kooky actor friends and a sad, aged Lugosi, Romero actually did employ regular people to portray zombies in his Living Dead series – many older native Pittsburghers will relate how their family members, friends, or co-workers were among the undead horde encroaching on the farmhouse in Night or on the Monroeville Mall in Dawn of the Dead.

As observed by many film critics and historians, this is likely what made Romero’s Living Dead films resonate with so many people, the indiscriminate notion that anyone could fall victim to zombification. That Romero also cast strong Black and female leads in these films further evolved them from their predecessors.

Romero, as far as I can tell, never credits Wood with influencing him. Even so, I can’t help but think that Wood, who was often mocked and dismissed for his off-beat choices, walked so Romero and others could run.